Federalism / Confederalism

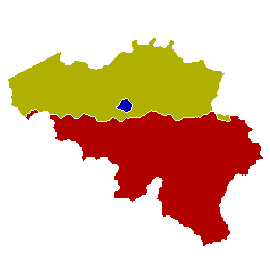

For quite a while now, there have been debates in Belgium about the form

its state ought to take. According to Article 1 of the Constitution,

Belgium “is a federal State composed of Communities and Regions”. Many

analyses have shown, however, that there are a few so-called “confederal

features” to the state system as well. Various political parties,

moreover, are calling – or have called – for Belgium to be transformed

in the next round of state reforms into a true confederation. But what

do the parties hope to achieve

through this appeal? Do they use the

term “confederalism” in the sense in which it is used in comparative

state law? Or are they thinking of something else, a confederalism

“Belgian style”? If the latter, what exactly does that consist of? This

contribution seeks to bring some conceptual clarity into the debate. The

classic theory of confederalism, about which there is widespread

consensus among lawyers, is taken as the golden thread. Confederalism

is, according to that theory, a relationship between states that agree,

in a treaty, to form a confederation in order to work together in a

number of different areas. This confederation is not itself a state, but

does have its own institutions that represent the participating states.

It has a limited number of powers assigned to it in the treaty. In

principle such a treaty can also be terminated. In this article, three

historical examples of confederation (the United States, Switzerland and

Germany) are considered, as well as the few confederations that still

exist today. Contemporary Belgium is not one of them. Rather, Belgium

today exhibits all the characteristics of a federal state. It is true

that the bipartite nature of the country, which is made up chiefly of

Flemish and French-speaking citizens, and the mechanisms available to

protect the French-speaking minority within the federal institutions (an

‘alarm bell’ and special majority provisions in Parliament, parity in

the cabinet), mean that the decision-making process in Parliament often

resembles a negotiation between the representatives of two political

communities. To qualify a state system as confederal, however, this is

not sufficient. The plans for a future “confederal” Belgium being put

forward by the political parties cover a multitude of meanings. They may

refer either to a deepening of the current form of federalism (e.g. by

allocating most of the powers to the constitutive states or by no longer

assigning residual powers to the federal state), or to a form of

confederalism in which the constitutive states enjoy the so called

“Kompetenz-Kompetenz”, and assign various competences to the

confederation by means of a treaty. For the sake of clarity in the

democratic debate, this contribution calls for greater conceptual

orthodoxy.

Available documents

Author

-

Jan Velaers